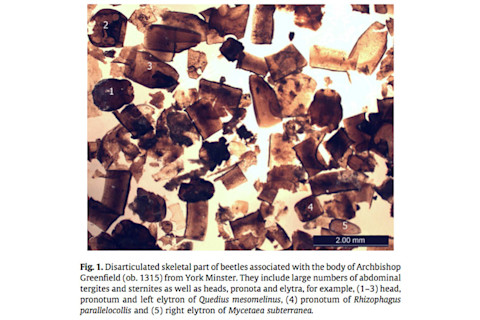

Archaeoentomology is a strange little corner of archaeology. Its practitioners search for signs of ancient bug life---fossilized eggs, old fly pupae, the like---in dig sites to tell, for instance, whether a body lay exposed before burial. One area they'd really like to know more about is what moves into coffins with bodies once they've, ah, started to go to earth. The worms crawl in, the worms crawl out, the worms play pinochle on your snout, to be sure, but which worms? So there's some interesting news in the latest issue of Forensic Science International for archaeoentomologists: researchers have produced a thorough catalogue of what was living inside the lead coffin of Archbishop William Greenfield shortly after he died in 1315

. (The coffin was disturbed during renovations to the church where it lies; the sample was taken then.) The researchers can't really say whether the list of long-dead insects whose parts they found means something particular about the bishop's body. But they present it as a case study of what moved in with the dead 700 years ago. In Greenfield's case, the answer is plenty of beetles, and the coffin beetle in particular, which is interesting, because you don't see those so much anymore. "Its decline in frequency may relate to the increased care taken in burial to a prescribed depth in sealed wooden coffins," the researchers point out. We don't know exactly what the beetle eats, they add: "There are differing opinions as to the beetle’s pabulum, whether it feeds on the fatty substances of the decomposing body, the coffin wood, fungi either found on the body itself or on the wood, or whether it is predatory on other inhabitants of the corpse." It's an interesting glimpse into the ecology of a burial, and also a reminder that lead coffins, unfortunately, don't do much to keep the creepy-crawlies out.