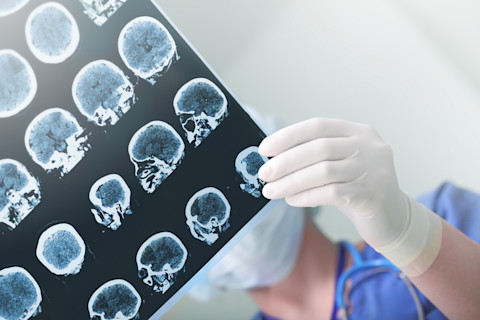

(Credit: Photographee.eu/Shutterstock) The dead, the headlines read, might soon be brought back to life. As pop-science headlines tend to, they blew the actual research proposal out of proportion, but the premise is real: The ReAnima Project recently received “ethical permission” from the government of India to take 20 patients who’ve been declared clinically brain dead, and try to restore a limited range of brain functions using cutting-edge neuroscience techniques. When we get past the knee-jerk references to zombies and Dr. Frankenstein, though, we’re left with the question of what this research is really about. Can scientists actually bring brain-dead patients back to life? Has anyone tried it before? And what does it mean, exactly, to resurrect a brain dead person? The answers to these questions reveal some surprising truths — not only about the frontiers of modern neuroscience, but also about our relationships with our dead and dying loved ones, and the ways we choose to define what a living human being is. As it turns out, "dead" people do tell tales.

Regeneration and Revival

Lines between life and death – and between consciousness and unconsciousness – are hardly black-and-white. In 2010, researchers made a splash with the announcement that they’d “talked” with patients in vegetative states, by way of fMRI brain-scanning machines that enabled the patients to give “yes” or “no” answers in the form of distinct brain activity patterns. Meanwhile, other teams of researchers have been working out ways to help brains trapped in comas and vegetative states rebuild themselves. “Repair and regeneration of nerve tissue is a big area for research,” says Dean Burnett, a neuroscientist at the University of Cardiff who studies the ethics of brain death cases. “But we're still unable to make it happen reliably.”

Brain death is more severe than a coma or a vegetative state. While a patient in a vegetative state can still breathe and digest food on their own, a brain dead patient’s body has lost the ability to function at all – even to maintain a heartbeat – without external assistance. Even so, a few cases of humans recovering from brain death – to varying degrees – have appeared in the scientific literature over the past 50 years. Two brain dead children briefly regained brainwave activity in 1975. A brain dead infant regained the ability to breathe in 1995. And in 2010, a 28-week fetus recovered completely from brain death, and was born healthy at 35 weeks. But all these cases are anecdotal, and none of the patients, aside from the 28-week-old fetus, recovered consciousness. Still, even in death – or what we define as death — a brain-dead patient still has a role to play in society.

The Living Dead

Brain-dead patients have served as research subjects for decades – mainly for studies on toxicology, organ transplants, and pharmacology. These patients, known as “living cadavers” in the medical community, have sparked controversy around the world. A 1986 paper in the Cornell Law Review argued that when a patient’s neocortex has ceased functioning they should be declared legally dead. These patients have lost the ability to sleep and wake, to form memories, to speak, and so on – even though their brain stem is still working. This isn’t just abstract theorizing. The University of Pittsburgh, the University of Chicago and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston have all been using “living cadavers” – with the consent of the patients’ families – to test experimental medical devices, to trace the paths of drugs through the body, and even to even let medical students to practice their surgical skills.

Other doctors would like to expand the definition of “death” to allow for an even broader range of “living cadaver” experiments. In 1996, an article in the British medical journal The Lancet proposed, “If the legal definition of death were to be changed to include comprehensive irreversible loss of higher brain function, it would be possible to take the life of a patient … then remove the organs needed for transplantation.” And in 2004, Belgian professor An Ravelingien went so far as to write, in the Journal of Medical Ethics, "If it can be agreed upon that bodies [in persistent vegetative states] can be regarded as dead, then experimenting on them is legitimate under the same conditions as experiments on cadavers.” Ravelingien isn’t even talking about brain-dead patients there; he’s referring to patients in persistent vegetative states, who still have measurable brain function. But a growing number of researchers are beginning to speculate that brain death may not be the end of the road for every patient. It’s an idea that’s new in medical science – but not in the world of biology.

Precedents in Nature

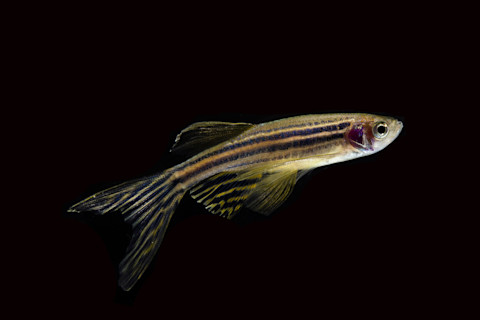

Many amphibians, fish, and even some mammals can regenerate large portions of their brains after severe trauma. They don’t need cutting-edge therapies or laboratory conditions to recover from brain death; they just sleep for a while and wake up with fresh brains. Why don’t humans and other primates have this regenerative ability? That’s one of the main questions the ReAnima teams are working to answer right now.

A scientists have observed neural regeneration in zebrafish. (Credit: suchetpong/Shutterstock) “There is no ‘magic bullet’ for reversing brain death,” says Ira Pastor, CEO of Bioquark, one of the companies involved in the ReAnima Project. “In this project, we’re employing a combination of biological regenerative tools, along with an array of medical devices used for stimulation of patients with other severe disorders of consciousness, such as comas and vegetative states.” Regenerating a brain-dead patient’s nervous system will not be a simple task. “Nature thrives on complexity,” says Pastor; and the ReAnima project’s goal is essentially to “train” severely damaged brains to rebuild themselves around whatever neural structure remains intact, using a combination of the latest therapeutic techniques. Repairing damaged nerve tissue, though, may be only one factor in revitalization.

Questions of Identity

“Our neural connections make us what we are,” says Burnett. “They underpin everything about a person.” Brain death damages many of those connections, and the brain further atrophies every day it remains in a brain-dead state. “To resurrect a person’s brain,” says Burnett, “these researchers would have to know how the brain was wired originally, down to a fantastically precise level, and coax the regenerating neurons to return to this arrangement.” It'd be a bit like trying to reassemble a book you’ve never read, after it's been burned. That might be true, Pastor says, if individuality boils down to nothing more than connections between neurons, but “based on several factors, we are placing our bets that the human mind is much more than that,” he says, “and on the idea that memory will be a recoverable commodity over time.” Many of our bodies’ cells die and are renewed thousands of times over our lives, yet we manage to hold onto our personalities – even those of us who suffer from Alzheimer's and other neurodegenerative diseases. Is brain death any different? That question remains, for now, an open one. We simply don’t know why some brain dead patients recover some functions, while others don’t. We’re not sure exactly how some animals regenerate severely damaged brains, or why humans can’t. And we still have very little idea what it would take, in total, to reconstitute a complete human personality. All we know for sure, so far, is that some animals – including a few humans – have recovered from brain death on their own. And any hope at all, Pastor says, is a hope worth pursuing. “If someone wants to criticize us for helping the family whose three-year-old child drowned in the pool, then so be it,” he says. “I’m very comfortable with the path I’m taking.”