What's the News: When prions or amyloids make the news, it's usually because they cause mad cow disease

or Alzheimer's

---prions

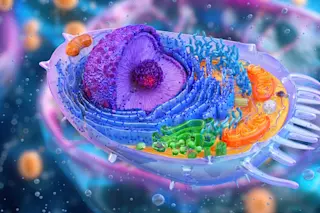

, after all, cause any proteins they touch to become as misfolded as they are, and amyloids

, which are large clumps of wadded-together proteins, can jam the workings of cells. But a new study in Cell suggests that a prion-like protein that forms amyloids has a normal, vital function in the brain

. Far from being a memory destroyer, this protein, called CPEB, is necessary for long-term memory in fruit flies.How the Heck:

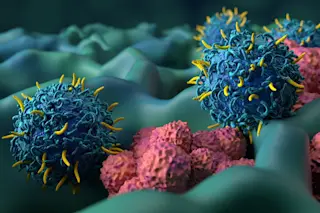

To see where the protein resides in the brain, the researchers added a fluorescent tag to the fruit fly version of CPEB, which is called Orb2A. They observed that Orb2A formed amyloids at synapses, the junctions between neurons---a promising sign that it could be involved in memory.

To see whether Orb2A was actually necessary for ...