When surgeons need to graft bone--for, say, reconstructing someone's face after an accident--they dig it out of another part of the patient's body, usually the pelvis. "It's a painful operation," says John Davies, a dentist and biomedical engineer at the University of Toronto. "And because the patient must undergo essentially two operations, he has to stay on the operating table for a longer time. That's more costly and means a longer recovery time."

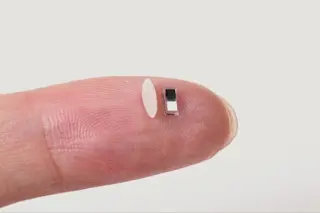

Davies and his colleagues have found a way to avoid that first, bone-harvesting operation. They've developed a polymer scaffold that mimics the structure of real bone. In particular, it's designed to work like trabecular bone--the spongy bone beneath the skeleton's hard outer shell. Like trabecular bone, the matrix has countless interconnected pores, each about a millimeter in size. Nestled within those pores are both osteoclasts (bone-eating cells) and osteoblasts (bone-making cells). When the synthetic bone is transplanted, ...