A sore back or sprained wrist makes your day-to-day life harder in more ways than one. Physical impairment is annoying enough on its own, but the chronic pain is its own distraction – one that makes it hard to focus. It’s been known for a while that chronic pain saps people’s motivation. And now, a team led by Stanford University’s Neil Schwartz has pinned down, in mice, some of the chemical and neural changes by which aches lead to ennui.

Tricky Treats

Schwartz and his team began by giving two different types of chronic pain to two sample groups of mice – one group got injections that caused soreness in their hind paws, while the other group received some minor surgical nerve damage. Researchers then had both groups compete against pain-free mice in a standard motivational test called a progressive ratio (PR) operant test, in which tasty treats become progressively harder to earn. In this study, the mice had to earn their rewards by poking a button with their noses – and some treats required more nose pokes than others. At first, all the mice were equally determined to earn their rewards. But after 21 days, the differences became striking: Mice that suffered from chronic soreness, whether from the injection or the nerve damage, were 40 percent less likely to try to earn treats than the mice without pain were – even after the pain-ridden mice were given an analgesic to dull their soreness.

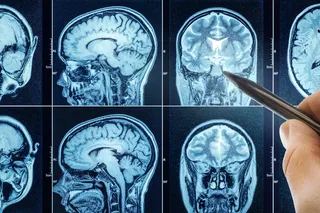

Brain Changes

The researchers then administered each type of chronic pain to half of a new sample group of mice, whose brains included a gene that made certain types of neural pathways glow under a special type of light. The investigators took samples from these mice’s brains, and looked for physical clues about this loss of motivation in brain areas known to be involved in reward-seeking behaviors. They found that the brains of mice with chronic pain changed in response to the discomfort. After 12 days of pain, certain types of neurons that respond to dopamine, a chemical involved in motivation and reward, were much less likely to send out excitatory signals than they were in pain-free mice. This could mean that a brain in chronic pain is physically less capable of getting motivated. This discovery raised an obvious question: What signals the brain to make these changes in its reward pathway? A chemical known as galanin looked like a likely culprit, since previous studies had linked it with bodily changes, in mice and in humans, in response to chronic pain. The researchers gathered two more sample groups of mice, and injected each group with a chemical that blocked the activity of galanin in a different way. The brains of mice whose galanin activity was blocked, the team found, changed less in response to chronic pain than the brains of mice with normal galanin activity did. They then tested galanin’s activity on the behavior of mice suffering chronic aches. They blocked the activity of galanin in a sample group of mice with chronic pain, and put these mice – along with another group with normal galanin activity – to the progressive ratio operant test. Mice with blocked galanin activity, the investigators found, performed much better after chronic pain than mice with normal galanin activity did. The results were published this week in Science.

Motivation Management

Interestingly, these motivational changes didn’t affect mice’s willingness to keep trying for easy rewards, only for treats that required lots of work. This may mean that chronic pain’s effects go relatively unnoticed until we come up against an unexpected challenge – and that’s when our motivation seems to suddenly fall apart. In addition to this psychological finding, the researchers now have a whole new toolbox of neurological discoveries that’ll likely come in handy for the development of advanced pain therapies. Blocking galanin activity in people may be a promising route to battling the brain changes wrought by chronic pain – helping keep our spirits high even in the face of life’s aches and pains.

Image by wavebreakmedia / Shutterstock