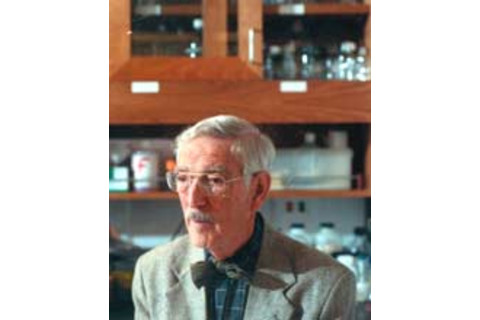

As the California sun descends on an afternoon social of wine, cheese, fruit punch, and Ping-Pong, National Medal of Science-winner and University of California at Berkeley biochemist Bruce Ames extols the virtues of pesticides to a former student. Pesticides allow fruits and vegetables to be produced more cheaply, he says, which means more poor people can afford to eat them. Poor people are most at risk for cancer, heart disease, and other ailments linked to diets low in fruits and vegetables. Hence, in the world according to Ames, pesticides confer a public-health advantage that far outweighs any health risk posed by their noxious residues. "If the EPA eliminates all the pesticides," he says, "all it's going to do is increase the price of fruits and vegetables, and there will be more cancer." "Isn't he great?" the student gushes. It's a typical reaction. Time and again in the course of his career, Ames, 73, has managed to deliver unpopular and even preposterous messages without denting his own credibility. Slender and mild-mannered, favoring striped shirts and cardigans, he has the bearing of a favorite uncle at a family reunion who tells silly jokes: "When I feel like exercise, I run my experiments, I skip controls, and I jump to conclusions." His track record helps silence detractors. Ames invented a simple test in the 1960s to identify cancer-causing chemicals that is still used worldwide. He has collected top honors in his field, published more than 450 scientific papers, and become one of the most cited scientists alive. Now Ames has decided to take on the most brow-raising research of his career: a scheme for physical and mental rejuvenation that relies mostly on common dietary supplements. His research group at Berkeley and at the nearby Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute has discovered a simple recipe that makes old rats think and act more like young ones. "If I'm lucky," Ames says, "we'll add a few years to human lives with this research." But luck is only one ingredient in Ames's success. He describes himself as a big-picture person, a so-so student who somehow made good in academia by assembling the byzantine details of other scientists' insights into coherent wholes. He never mentions hard work. Although well past the age of retirement, Ames still lives for the lab. "I told a friend that I was doing the best work of my career," he says, "and he said I had been telling him that for 30 years."

"Getting old is just like getting irradiated," says Bruce Ames, whose quest during the twilight of his career is to find ways to combat—and possibly reverse—the destructive effects of ordinary cellular metabolism.

In the 1950s, Ames began working at the National Institutes of Health, where he was investigating ways of mutating the DNA of bacteria in order to learn more about gene regulation. His work led him to develop a petri-dish protocol for testing whether a substance can cause such mutations. With that test, Ames and other investigators were able to show that most cancer-causing chemicals act by damaging genes—a finding that now seems obvious only because Ames helped prove it. "This test you can do in an afternoon, whereas an animal cancer test costs a million dollars and takes two years to do," he says. "I never patented it, so I never made any money out of it." But Ames had made a reputation. In the late 1960s, he took that reputation to Berkeley, where he continued his cancer studies. In one of his classes, he invited students to run the Ames mutagenicity test on substances they routinely used. "They would bring in birth control pills, marijuana, things that were interesting to them," he says. "But one day, one of the students brought in hair dye. And it was screamingly mutagenic." Ames identified the culpable compounds, and dye manufacturers eliminated them. He went on to demonstrate that the flame-retardants then used in children's clothing were also mutagens. A concerned young mother named Lois Gold contacted Ames after his findings were reported in the local paper. Impressed by her questions and her background in statistics, Ames hired her to help him create an exhaustive compendium on the toxicity of everyday and industrial chemicals. "She didn't know anything about science, but she was very logical and very persistent, wanting to know every little thing," he recalls. "I like people around me who want every i dotted and t crossed." The carcinogenic potency database has become an institution, and Gold still runs it. But as Ames reviewed the results of animal tests for the database, his stance on cancer-causing chemicals shifted. He and Gold have shown that half of all chemicals, whether natural or synthetic, cause cancer in animals if they are delivered in high doses. Mold toxins, plant-made pesticides, and compounds in roasted coffee, for example, test positive in rodent carcinogen assays. Yet people are rarely subjected to such extreme levels. Ames came to believe that too much of anything, even a good thing, might stress a body enough to cause cancer. The high doses of compounds used in tests on rats, he says, are therefore meaningless. "Nobody ever really did the controls—they didn't test a random set of natural chemicals," he says. "We think half the chemicals in the world are going to be carcinogens when you test them at these huge doses. So what we're saying is not that natural chemicals are particularly dangerous, but that those are most of the chemicals you get into you, and the hit rate is exactly the same." Nor is Ames saying that all man-made chemicals are safe; he just thinks public health priorities have become skewed. More lives would be saved, he insists, if the money spent on regulating pesticides and industrial waste were channeled instead into campaigns to eliminate smoking and improve nutrition. "I just view it all as some terrible distraction," he says. "People are being done in by their own behavior: eating, drinking, smoking." "I don't think anyone will deny that diet is important," says Ronald Melnick, a toxicologist at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences who has coauthored a lengthy rebuttal of Ames's claims. "But what he says is: 'Eat your spinach, and don't worry about whether there's pesticide on it.' But why not eat very low levels of pesticide on your spinach? You can have both." Affordable produce grown with pesticides, Melnick says, could be made safer if farmers or consumers got serious about washing off chemical residues. "It's not a matter of one or the other. We need to address both issues." Melnick also argues that animal studies include doses at various levels in order to establish cause and effect. "It's an overgeneralization to say that every study is done at high doses. We try to make a judgment of what dose could be used without causing significant tissue damage. It's not just a matter of pumping in as much as you can." In any case, Melnick and his colleagues say, there's no alternative to animal testing, short of waiting 30 years to see if people exposed to suspect chemicals get cancer. Harvard University epidemiologist Walter Willett says Ames is "obviously playing a role—and somebody in science has to do it—where sometimes you need to state things provocatively to stir up the pot and get people to look critically at issues they weren't looking at before."

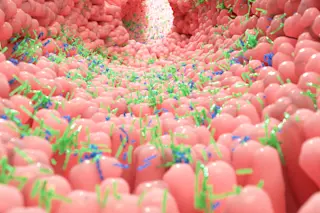

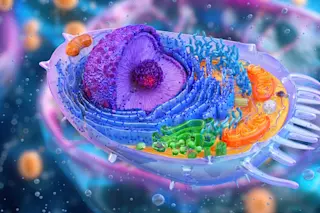

As Ames neared 65, his thoughts turned to the notion of aging. He wasn't contemplating retirement, grandchildren, or Palm Beach. His studies of cancer-causing chemicals had instead led him to consider a group of substances that often prove troublesome to folks of his vintage: free radicals. Free radicals are highly reactive molecules that ravage the innards of cells. Free refers to the fact that these compounds are misfits, with no proper place in cellular society. Radical is the name biochemists give to an atom or molecule with an unpaired electron. Unattached free radicals bond indiscriminately with other molecules, stripping them of electrons with disastrous results—broken chromosomes, crippled enzymes, and punctured membranes. The electron-stripping process is called oxidation, and in controlled circumstances it's a vital part of ordinary cellular metabolism. But free radicals are more like toxic waste. They leak from energy-making organelles called mitochondria; they spew from disease-fighting blood cells. Although cells have built-in mechanisms for cleaning up free radicals, the oxidants ultimately get the upper hand. In the mid-1950s, Denham Harman, a physician and chemist in the Donner Laboratory of medical physics at Berkeley, proposed that the cumulative damage wreaked by free radicals was largely responsible for the aging process. Today his free-radical theory is the most widely accepted model of aging. Ames got interested in free radicals because they can cause cancer. Like radiation and carcinogens, free-radical oxidation breaks strands of DNA. The breaks are repaired, but some mistakes occur. Mistakes in DNA coding are also known as mutations. And as Ames had helped demonstrate, certain genetic mutations predispose an individual to certain cancers. No one knows why, but the incidence of most cancers increases with age. Ames thought the age-related increase in cancer rates might have something to do with an age-related rise in oxidative damage to DNA. But no one had shown that DNA oxidation actually does increase with age. In 1990 Ames and his colleagues at Berkeley published the first evidence that it might. They found twice as much DNA oxidation in the tissues of 2-year-old rats as in those from 2-month-old rats. Ames's research on oxidation led him to look more closely at mitochondria because they are the mother lode of free radicals. In order to burn fats and carbohydrates to make metabolic fuel, mitochondria take electrons from oxygen and shuffle them among a suite of molecules in a complex chain reaction. Invariably, some of the electrons get misplaced, creating free radicals. "People have estimated that [the electron transport chain] is maybe 98 percent efficient, which is much better than a human engineer can do," says Ames. "But it still makes kilos of oxygen radicals per person per year." Mitochondria produce more oxidants than any other single site in a cell, the main offenders being superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals. Ames thought mitochondria would therefore be hardest hit by free-radical damage, not only to mitochondrial DNA but also to enzymes in the electron transport chain and lipids in mitochondrial membranes. It also occurred to him that mitochondria might be an ideal target for intervening in the aging process. Working with postdoctoral student Tory Hagen, Ames characterized the changes that occur in the mitochondria of aging rats. They have shown that old mitochondria consume less oxygen, have stiffer membranes, and shuffle electrons less efficiently than their younger counterparts. Old mitochondria also make a lot more oxidants.

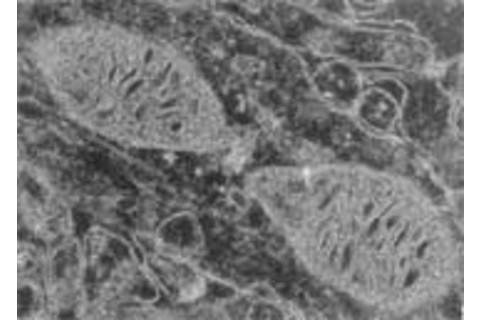

Mitochondria are the structures in which the chemical reactions that power a cell occur, and they undergo age-related damage from metabolism. When comparing a young rat's brain cell (above) with an old rat's brain cell (below), the deterioration of mitochondria—the large sausage-shaped objects—is visibly apparent. A human brain cell may house well over a thousand mitochondria. Each one reproduces independently and lives for about two weeks.

Photographs courtesy of Dr. Jiankang Liu.

If he chose to, Bruce Ames could trace his next antiaging breakthrough to a decision he'd made 40 years before, when he proposed to Giovanna Ferro-Luzzi, who was then a biochemist at the National Institutes of Health. Ames is still madly in love with his wife and with her native country. The couple own a house in Tuscany and an apartment in Rome. In the mid-1990s, a dietary supplement called acetyl-L-carnitine became all the rage in Italy. Ames took notice. "It sold as a pick-me-up. You'd think Italians would get picked up with espresso," he says. Researchers at the University of Bari in Italy had reported that feeding acetyl-L-carnitine to old rats improves the function of their mitochondria. Stateside, no one but Ames paid much attention to the report. He could see how the supplement might achieve its effects: Acetyl-L-carnitine, also known as Alcar, is a nutrient that helps transport fatty-acid fuel across lipid membranes into mitochondria. Thus the more Alcar a cell has, the better its mitochondria might function. Ames reasoned that high levels of Alcar might also combat the problems of aging membranes and decrepit enzymes. He began feeding Alcar to his old rats. Within weeks, he and Hagen noticed improvements in the animals' biochemistry and behavior. Their mitochondria were going full bore again, and they had become far more active. But the old rats were still churning out oxidants at a very high rate. In fact, by goosing metabolism, Alcar seemed to slightly increase free-radical production. "We didn't solve the problem of oxidants," Ames says. "In fact, if anything, it was a little worse." Ames decided to add an agent to the rats' diet to neutralize the oxidants. He tried lipoic acid, a mitochondrial antioxidant. The results were profound. Oxidants and oxidative damage to mitochondrial components dropped dramatically. Both the structure and function of the mitochondria improved. The rats' activity levels doubled. They were, Ames says, "doing the Macarena." The combination of the nutrient and the antioxidant had a synergistic effect. "The two together are better than either one alone." But the most exciting changes were in the rats' brains. Ames, Hagen, and another postdoc, Jiankang Liu, tested the memory of old rats by training them to find a platform submerged in a swimming tank. Rats are good but reluctant swimmers, so they're motivated to learn. Without supplementation, "the old ones are wandering all over the place before they find the hidden platform," Ames says. "The young ones make a beeline for it." With just a month of Ames's antiaging combo, old rats get to the platform almost as fast as young ones. The old rats' performance on other kinds of memory tests also improves, showing that the swimming-tank test isn't just measuring sharper eyesight. Ames is waiting to see whether they live longer too.

So far, Ames's latest project has been greeted with less skepticism than might be expected. "It was surprising to a lot of people, but it's something that he has documented well," says Earl Stadtman, an expert on protein oxidation and aging and a former colleague of Ames's at the National Institutes of Health. "I don't think there's any reason to doubt [his findings]—I don't doubt anything that Bruce does, because I've followed his research over the years, and it's been very solid." The public may soon be conducting its own reviews. Three years ago, Ames set up a company called Juvenon to test the antiaging duo in human beings. But it's not exactly a proprietary blend. Both ingredients—Alcar and lipoic acid—are already marketed as dietary supplements. Consumers can even duplicate the dosages used in Juvenon's trials: 200 milligrams alpha-lipoic acid and 500 milligrams acetyl-L-carnitine, twice a day. "There's nothing to prevent a health-food store from putting a bottle of acetyl-L-carnitine on a shelf, putting a bottle of lipoic acid next to it, and putting our paper up above it," Ames admits. But in this country, dietary supplements are not tightly regulated to ensure that the products contain the advertised doses and ingredients. And Ames won't know the optimal dose of each supplement until the trials' completion. Meanwhile, he's identified other common nutrients that may also reverse aging. "There will be other things to add to this mixture," he says. "This is just the beginning of getting a really good aging-intervention therapy." Ames is convinced that simple B vitamin therapy could also combat some cases of migraines, mental retardation, and many other maladies. In a subset of patients with each disease, Ames believes the same underlying mechanism is at work: Genetic mutations result in deformed enzymes that don't work as well as normal ones. Enzymes rely on molecular partners called coenzymes to do their job. High amounts of B vitamins can boost levels of coenzymes, thereby improving the binding function of defective enzymes. Ames has published an exhaustive review, with more than 300 references, showing that no fewer than 50 genetic diseases might be remedied with high doses of vitamins, minerals, and amino acids. "He's pulled together a lot of information from different fields," Willett says. "This is going to keep 500 scientists working hard for the next 50 years in order to sort it all out." True to his role as provocateur, Ames likes to illustrate the enzyme concept with a somewhat preposterous example. Half of all Asians can't tolerate alcohol, he notes, because of a hereditary deformation in an enzyme that regulates alcohol metabolism. That enzyme relies on a helper molecule called NAD that, in turn, contains dietary niacin. Treatment with niacin increases NAD levels and might overcome the enzyme deficiency. "I know you can feed people high niacin and raise NAD levels," says Ames, "but no one else knows it. I thought briefly of patenting a Japanese beer with niacin. You could get all the Japanese drunk." In the future Ames envisions, people will be screened individually for genetic mutations and micronutrient deficiencies, and dietary interventions will be customized. Ames and his colleagues have already devised a DNA test that can quickly assess oxidative damage to a person's genes. But those tests aren't cheap, and multivitamins are. As a more practical measure, he recommends a healthy diet and a daily multivitamin; he takes one every day himself. "To do an analysis on each person would cost hundreds of dollars, and yet it's a penny for a multivitamin," he says. Ames doesn't stand to profit either way. He has no financial stake in Juvenon, and Berkeley gets most of the proceeds from his patents. But Ames unwittingly assured himself a pension several years ago when he wrote a $100,000 check to a former student who was starting a biotech company in California. The company sold for $100 million in 2000. Ames gave $8 million of his newfound wealth to start a genomics and nutrition center. He gave his department at Berkeley a couple million for improvements there, and he doled out thousands more to research projects. With the rest, he set up a foundation to conduct outreach programs to improve nutrition among the poor. "If I'm going to get vitamins in the poor, I guess I'm going to have to do it myself," he says. Meanwhile, he says his goal is to extend functional years rather than longevity per se. Yet when he strays from his discourse on mitochondrial membranes and antioxidants, he gives the impression that the secret to his own long, happy history doesn't come from a pill bottle. "I'm so content, I'm just purring in my life now," he says. "I have a wonderfully happy marriage. I'm doing very well in my career. And then I just got all this money. But who needs money?"

Ames believes that his team's studies of the effects of dietary supplements in aging rats could lead to a new appreciation of nutrition. "I'm very excited about the idea of tuning up our biochemistry—someday it may be as big a thing as pharmaceuticals."