In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, but the revolutionary antibiotic didn’t reach the masses until 1945, after two Oxford scientists developed the necessary large-scale production method.

In the intervening 17 years between discovery and distribution, Fleming continued to experiment with small batches of penicillin on several bacterial pathogens, including Staphylococcus. In the process, he unearthed the earliest signs of a phenomenon that now plagues medicine almost a century later: the ability of bacteria to become resistant, even immune, to antibiotics.

He identified this potential for resistance in 1940, just five years before penicillin became available for widespread use, and he received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for its discovery.

‘‘I would like to sound one note of warning. ... It is not difficult to make microbes resistant to penicillin in the laboratory by exposing them to concentrations not sufficient to kill them, and the same thing has occasionally happened in the body.’’

— Alexander Fleming, 1945

Ever since Fleming’s first glimpses of trouble, researchers have consistently run into the same thing after releasing antibiotics. When tetracycline hit the market in 1950, for example, it was an immediate godsend for people diagnosed with several bacterial infections, including Shigella, an intestinal bug that can cause 20-plus bouts of diarrhea a day. But by 1959, strains of Shigella had already developed resistance to tetracycline.

Those therapeutic windows soon began to close even faster. It took only two years for a strain of Staphylococcus to become resistant to methicillin after that drug was introduced in 1960. In 1996, when levofloxacin hit prescription pads, a strain of pneumococcus became resistant to it that very year.

The latest statistics also tell dire tales. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conservatively estimates that in the United States, more than 2 million people are sickened each year with antibiotic-resistant infections, and at least 23,000 die from them. When you include Europe, infections that resist antibiotics raise the death toll to at least 50,000 people annually. Add in the rest of the world, and that becomes many more hundreds of thousands.

‘‘We didn’t give bacteria credit for being able to change and adapt so fast. Basically, bacteria do evolution on a 20-minute time scale. It takes humans about 20 years to make an offspring, but bacteria are dividing every 20 minutes, testing out new mutations for selective advantages.’’

— Bonnie Bassler, chair, Department of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, 2009

For Bacteria, Resistance Is Not Futile

So how do bacteria become resistant to antibiotics? The real question is: How can they not?

Measured solely by longevity, bacteria are wildly successful. They were present for the dawn of life on this planet, an event as long ago as 3.5 billion years. We are the ones living in their world, and in evolutionary terms, they’re much better at surviving in it than we are.

In other words, the very act of using antibiotics is what inevitably leads to the drugs’ defeat. Each time they are exposed to the pharmaceuticals, bacteria have an opportunity to create mechanisms of defense. And, given frequent enough exposures, they almost always do.

A Chain of Resistance

All it takes are a few hardy bacteria to survive antibiotics given to animals, and resistance is off and running. That resistant bacteria can spread and affect the human food supply.

So Now What? Well, There’s Plan B, and C and D …

In January 2015, an international team of scientists led by Kim Lewis at Northeastern University in Boston published a study on the discovery of a new antibiotic. Called teixobactin, it kills pathogens without any sign that it promotes resistance while doing so.

Although it’s still years from human trials, teixobactin has shown huge promise by decimating highly resistant staph strains of bacteria in mice. But that’s not even the most exciting part. This is: The researchers found teixobactin by combing through a gram of plain old dirt. They then cultivated the bacterium that makes it, Eleftheria terrae, using a revolutionary new process.

It’s important to remember that, in the din of all the doom-speak, there are smart people working on smart solutions to antibiotic resistance. Here are some others:

Phage Therapy

What it is: Discovered in the early 1900s, bacteriophages, or phages, are a specific group of viruses with a purpose that is given away by translating their name from Latin to English: “bacteria eaters.”

How it works: Practitioners select a virus or combination of viruses that will treat a person’s specific bacterial infection. The patient usually takes the phages in pill or powder form, or applies them as an ointment. If the viruses are well chosen, they go to work infecting and killing the pathogenic bacteria without harming other cells.

Drawbacks: The practice of phage therapy has been honed primarily in the former Soviet bloc countries of Russia, Georgia and Poland, where Western antibiotics were scarce until after the fall of the Iron Curtain. Here in the U.S., FDA regulations prohibit most phage therapies if they haven’t gone through the approval process of clinical trials, so many treatments aren’t available. That is beginning to change, though. In 2014, the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases threw its support behind phage therapy, and researchers at MIT are working on a phage engineered to deliver killer DNA specifically to antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Boosting Antibiotics

What it is: Bacteria almost always develop resistance to antibiotics if given enough exposure. And since most antibiotics currently in use are souped-up versions of previous ones, strengthening the rest may be the quickest path to dealing with resistance.

How it works: There is a considerable lag period between starting work on a drug and bringing it to market. So the first step is to keep existing antibiotics effective longer by limiting exposure. Despite extensive educational campaigns, the CDC estimates antibiotics still aren’t prescribed properly about half the time — for wrong conditions, in incorrect doses or for ineffective durations. The second step is to place increased emphasis and added incentives on identifying ways to provide a boost to existing antibiotics.

Drawbacks: Time and money. Time can be bought — by reducing ineffective prescriptions in humans and eliminating almost all antibiotic use in agriculture. Money can be allocated — it costs hundreds of millions of dollars to bring a new drug to market, even one based on an existing version. For several reasons, pharmaceutical companies have rarely been willing to make that kind of investment for antibiotics, likely leaving the funding gap in the hands of other organizations such as government agencies and universities.

Quorum-Sensing Inhibition

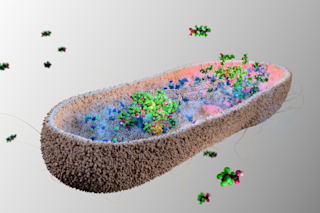

What it is: This may flip your lid a little: Bacteria talk to each other — a lot. They live in close-knit communities they build themselves out of a substance called biofilm. By emitting a constant stream of signal molecules, they can communicate with their neighbors about important issues such as whether to reproduce enough to cause an infection in their host. Even more amazingly, they can do all these things only if they know they have a quorum — enough fellow bacteria to take on whatever tasks are at hand.

How it works: Quorum- sensing inhibitors disrupt or divert the signaling molecules bacteria use to sense when they’ve reached a quorum. If the bugs can’t tell if there are enough others around to cause mass mischief, they float in isolated ignorance until the host gets rid of them. When this happens, they can’t cause infections requiring antibiotics, much less antibiotic-resistant infections.

Drawbacks: Despite more than 15 years of fairly extensive research, microbiologists have been unable to find anti-quorum-sensing compounds that work consistently and reliably in animal models, let alone human ones. The theory remains solid, but workable therapies are years away

From Farm to Table

In 2011, Americans used 7.7 million pounds of antibiotics. In the same year, farm animals in the U.S. were fed nearly four times that amount: 29.9 million pounds.

That has real consequences. Two years ago, Consumer Reports tested chicken breasts it bought from stores across the country and found that about half were contaminated with bacterial strains resistant to three or more antibiotics commonly prescribed to people. And at the end of last year, Chinese researchers found a strain of E. coli in farmed pigs that was highly resistant to polymyxins, the group of last-resort antibiotics used in humans when all others have failed.

Viva La Resistance

These 18 bugs comprise a rogues’ gallery of microorganisms showing various levels of resistance to the best available antibiotics. The CDC categorizes each by level of threat: urgent, serious or concerning.

Urgent

Clostridium difficile

In the U.S., almost half a million people are sickened by chronic diarrhea caused by a C. difficile overgrowth. About 15,000 will die each year.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae

“CRE are nightmare bacteria,” warns Tom Frieden, director of the CDC. “Our strongest antibiotics don’t work.” Development of a CRE infection in a hospital is deadly nearly 50 percent of the time. The infamous E. coli is part of this group.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

The same N. gonorrhoeae known in medieval times as the “perilous infirmity of burning” now infects 820,000 Americans each year. A third of those will get the drug-resistant strain of gonorrhea, a condition that may soon be untreatable.

Serious

Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter

An opportunistic infection that strikes those already critically ill with another condition, it affects about 12,000 Americans. At least three different classes of antibiotics are no longer effective against Acinetobacter.

Drug-resistant Campylobacter

There are at least 1.3 million infections by Campylobacter in the U.S. each year, usually from eating tainted food. A quarter are resistant to antibiotics.

Fluconazole-resistant Candida

Although not a bacterium, the fungus Candida is outrunning the drug fluconazole’s ability to kill it; overgrowths can cause bacterial bloodstream infections and sepsis.

Extended spectrum beta-lactamase Enterobacteriaceae A broad class of microbes that can cause urinary tract infections and pneumonia. It is quickly developing immunity to the strongest antibiotics.

Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus

Enterococci bugs thrive in hospitals, causing surgical infections or other complications. About 1 in 3 infections are resistant to the go-to antibiotic, vancomycin.

Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Another bacterium commonly found in hospital-acquired infections. Of the 51,000 infections each year, 6,700 are resistant to multiple antibiotics.

Drug-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella

These bacteria are behind food poisoning at its cruelest: 1.2 million annual cases of extreme gastrointestinal woe. A tenth of cases are resistant to antibiotics.

Drug-resistant Shigella

Of the half-million annual infections in the U.S., 27,000 resist antibiotics, a chronic consequence of which can be a potentially lifelong form of arthritis.

Methilillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

One of the ugliest of superbugs, MRSA can cause everything from deadly pneumonia to disfiguring skin infections. It kills over 11,000 Americans each year, about 1 in 7 who are infected with it.

Drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae

S. pneumoniae is the No. 1 cause of bacterial pneumonia and meningitis in the country. It also causes lesser infections of the ear and sinus. Of the 1.2 million infections each year, 7,000 are fatal.

Drug-resistant tuberculosis Emerging over 70,000 years ago, tuberculosis has been called history’s biggest killer. In the early 1900s, 1 out of 7 people in the U.S. and Europe died from what was then called consumption, while others were quarantined for life in a sanitarium. The discovery of streptomycin in 1943, the first antibiotic effective against TB, coupled with later antibiotics, nearly eradicated the disease. But now it’s clawing its way back. Of the 10,500 cases each year in the U.S., over a thousand don’t respond well — or at all — to antibiotics.

Concerning

Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

S. aureus lives on skin, where it is harmless. But it can enter the body through a medical procedure, such as catheter insertion, and cause a systemic infection. This happens very rarely, and no treatment options exist.

Erythromycin-resistant Gropu A Streptococcus

This is a menace of many masks — among them strep throat, scarlet fever, rheumatic fever, toxic shock syndrome and flesh-eating disease. About 1,300 such infections prove drug-resistant each year, and 160 are fatal.

Clindamycin-resistant Group B Streptococcus

Group B strep infections sicken at least 27,000 Americans annually, of whom 7,600 don’t respond well to antibiotics. About 440 of those people will die.