What will the organ transplants of the future look like? Researchers in Tokyo suggest something that resembles injectable strings able to integrate themselves organically into the human system.

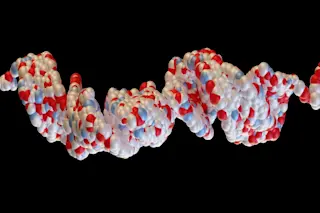

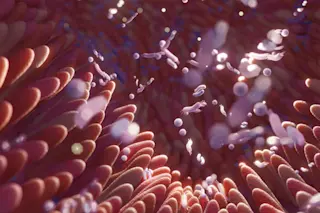

Scientists' initial tests of this cell-laden fiber produced working heart, vein and nerve tissues, and even regulated diabetes in living mice. The production process begins with a straw-like tube of modified gelatin called a hydrogel. This is filled with fibers made of natural proteins like collagen and fibrin, which are part of the extracellular matrix that gives animal cells their structure. Within the fibers are primary cells, such as endothelial cells, myocytes or nerve cells.

The result of this combination is a kind of safe space for cells to grow. The fibers create a life-like microenvironment in which the cells can function and interact with each other just like normal cells would, while the hydrogel protects them from the body's immune response.

...