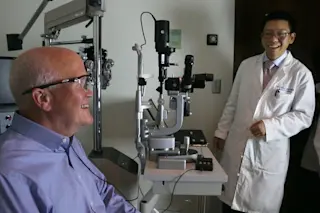

Larry Hester and Paul Hahn, MD, prepare for the first test run with the new bionic eye. (Photo Credit: Shawn Rocco at Duke Medicine) People diagnosed with a degenerative eye disease are seeing a new future thanks to bionic eye technology. For decades, Larry Hester adjusted to life without vision after retinitis pigmentosa caused the photoreceptor cells in his eyes to gradually die off. But this week, Hester’s sight was partially restored following surgery that transformed his eye into a bionic eye. He’s now the seventh person to undergo this FDA-approved procedure. Hester received the device in September, but he tested his bionic eye for the first time yesterday — as captured in the video below:

The device Hester uses to see is called the Argus II Retinal Prosthesis system, which the FDA approved for use in patients with advanced retinitis pigmentosa last year. The disease affects about 100,000 people ...