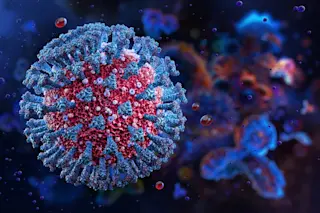

This past year will be remembered as a watershed year for AIDS research. Among the breakthroughs was the finding, in August, that a mutation in the ckr-5 gene, which encodes the receptor that the virus uses as a doorway into a cell, provided resistance to hiv infection. Then, in September, the surprising extent of that resistance was documented by population geneticist Stephen O’Brien and his colleagues at the National Cancer Institute, who studied 1,955 people at high risk for contracting the virus.

Roughly 1 percent of the study group carried two copies of the mutated ckr-5 gene, says O’Brien--and they had all resisted infection despite multiple exposures to hiv. A much larger percentage--about 14 percent--carried one mutated ckr-5 gene. Although these people could and did become infected with hiv, the progression from asymptomatic infection to aids was likely to take two to three years longer in them than in a ...