Typhoon Lekima blasted ashore south of the mega-city of Shanghai early on Saturday local time, whipping the coast with sustained winds of around 115 miles per hour.

A million people were evacuated ahead of the storm, which has caused 13 deaths. Now a tropical storm, Lekima is churning north through eastern China, raising risks for major flooding and mud slides.

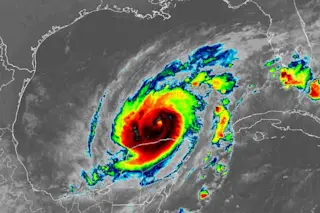

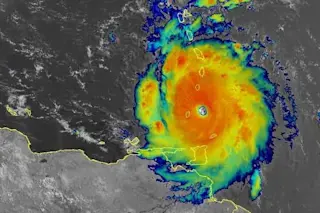

The animation of Himawari-8 satellite imagery above shows Typhoon Lekima on Thursday, Aug. 8 as it was passing through the Ryukyu Islands of southern Japan. It documents dramatic behavior by the eye of the storm. So be sure to click on the screenshot, and then be a little patient if it takes a moment for the high-resolution animation to load.

At the start of the infrared view, Lekima whirls northwestward, looking all the world like a buzzsaw aimed at Ishigaki Island, home to one of Japan’s southernmost cities. At the ...