Update: I posed some questions related to this story to Jason Furtado, a meteorologist at the University of Oklahoma. I've added them and Furtado's responses to the end of the post.

In a first, researchers have used chemical fingerprints locked within coral skeletons to build a season-by-season record of El Niño episodes dating back 400 years — a feat many experts regarded as impossible. That record, presented in a new study appearing in the scientific journal Nature Geoscience, reveals an "extraordinary change" in the behavior of El Niño, according to the researchers. That shift "has serious implications for societies and ecosystems around the world."

To conduct their study, lead author Mandy Freund and her colleagues relied on coral records collected by many scientists around the tropical Pacific over the course of decades. The records consists of cores drilled from coral skeletons. As living corals grow, they build their skeletons from compounds drawn from the water, building up bands on a seasonal and even biweekly timescale, much as trees add growth rings every year.

These layers contain chemical fingerprints that can be used to deduce the climatic conditions that existed when the bands were laid down — including conditions indicative of El Niño episodes. Using these records, Freund and her colleagues were able to use a machine learning technique to tease out what kinds of El Niño events have occurred over the past four centuries. As it turns out, El Niño is not a single phenomenon. It come in different flavors.

The traditional one features abnormally warm surface waters along the equator in the eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. When that warmth builds up, weather patterns are disrupted in many far-flung parts of the world.

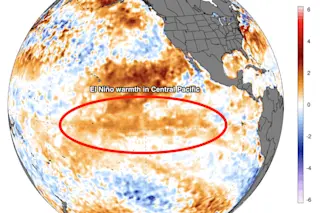

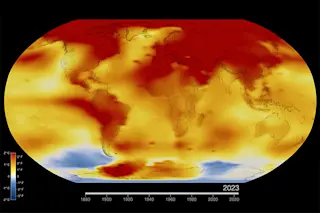

But there's also another flavor, one featuring anomalous warmth in the central tropical Pacific. You can see this phenomenon in the image at the top of this post. It shows a pool of warm surface water stretching along the equator in the central portion of the ocean. That warmth is indicative of mild El Niño conditions that have been in place for several months and are expected to last into the summer and possibly into the fall.

This particular El Niño flavor "has become far more prevalent in the last few decades than at any time in the past four centuries," Freund and her colleagues write in an article about their research published it The Conversation. At the same time, traditional eastern Pacific El Niños have become even more intense.

"Some climate model studies suggest this recent change in El Niño 'flavours' could be due to climate change, but until now, long-term observations were limited," according to Mandy her colleagues.

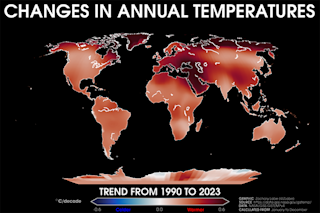

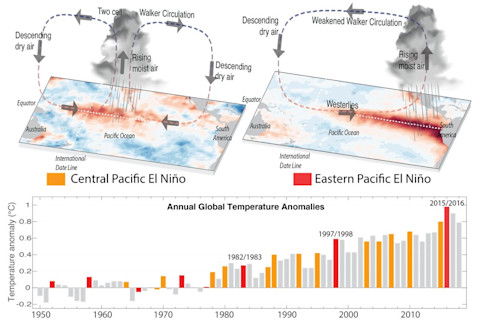

A schematic of idealised atmospheric and sea surface temperature conditions during El Niño events in the central Pacific (top left) and eastern Pacific (top right). Annual global temperature anomalies (lower panel) show the global warming trend. Many of the hottest years on record coincide with El Niño events. (Credit: NOAA National Centers for Environmental information, Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series)

NOAA National Centers for Environmental information, Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series

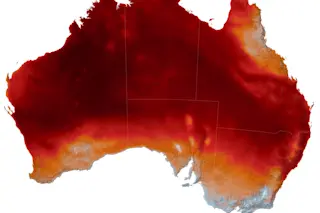

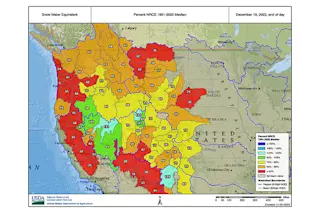

The top panel in the graphic above illustrates the difference between the two kinds of El Niños and shows how they result in different patterns of atmospheric circulation and resulting rainfall. These factors in turn have significant, far-reaching effects on weather, stretching from Australia and Asia to South America and up into North America.

The bottom panel illustrates the relative abundance of central Pacific events. It also shows the super El Niño of 2015/2016 — a traditional eastern El Niño — that gave human-caused warming an extra boost, driving the global average temperature up to a record high. With only a few exceptions, the two kinds of El Niño events were about equally as common prior to the 1980s, as illustrated in this graphic showing the ratio of the two over the past 400 years:

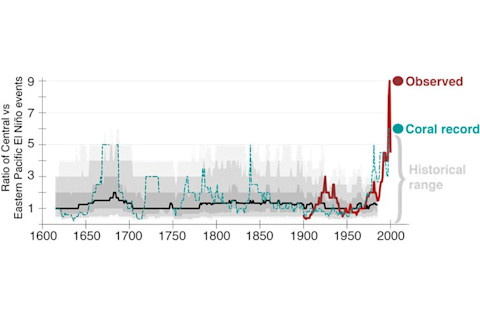

The ratio of central Pacific El Niños compared to eastern Pacific events over the past 400 years, expressed as the number of events in 30-year sliding windows. The red line illustrates the rise of central El Niños since 1980. (Credit: Mandy Freund et al from The Conversation.)

Mandy Freund et al from The Conversation.

The intensity of both types of events remained relatively stable over the past four centuries. And in general, central El Niños were weaker than eastern ones. But that began to change after about 1980. The study shows that central Pacific El Niños have more than doubled compared to the preinstrumental average, from 3.5 to 9 events every 30 years. At the same time, the number of eastern El Niños has been lower over the long run, with about two events every 30 years — even as their intensity grew. The new findings are one step toward more confident predictions of El Niño's behavior as the climate continues to change under the influence of humans.

Below are the questions I posed by email to Jason Furtado, a meteorologist at the University of Oklahoma who focuses on large-scale climate dynamics, and his answers. (Note: In his answers, "SST" refers to "sea surface temperatures." And "ENSO" is an abbreviation for "El Niño-Southern Oscillation," the broader phenomenon that includes La Niña — El Niño's opposite.)

Question: Last July you wrote that if an El Niño were to develop, as seemed increasingly likely back then, conditions in the South Pacific suggested it would be a “‘weak' or CP event.” We are now in an El Niño, and I think readers would be interested to know whether it is indeed a CP event.

Answer: The El Niño event that developed this past winter was characterized as a weak El Niño event. If you look at the map of the sea surface temperature anomalies in the tropical Pacific averaged over the winter months, the structure resembles that of a Central Pacific-like El Niño event, though there were still some warmer than normal waters further to the east. The current SST anomalies are also confined to the central tropical Pacific.

Question: If you’ve had a chance to read the Nature Geosciences paper, I’d be curious to hear your reaction to it. Particularly how much stock we can put in the coral records used to reconstruct the El Niño phenomenon going back 400 years.

Answer: Paleoclimate reconstructions of El Niño are common in the paleoclimate literature, especially with corals. In fact, out of all different types of paleoclimate records available for reconstructing tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures in the past, corals offer some of the best records because their growth rates and chemical composition is directly related to SSTs in the region where the corals are found. So, yes, I trust the veracity of these coral records and the message they show.

Question: What of the evidence suggesting that CP El Niños should continue increasing in frequency thanks to climate change? How robust is that research? And do we know what mechanism connects anthropogenic warming to this trend?

Answer: This paleoclimate study agrees with what several climate models also indicate about the future of El Niño – that is, the trend toward a higher frequency of central Pacific El Niño events through the 21^st century. Models suggest overall strengthening of eastern Pacific (or “traditional”) El Niño events as well.

Question What might this mean for El Niño’s impact on weather phenomena?

Answer: Several studies (including ones that I have done) have recognized that the winter weather patterns (or teleconnections, as we call them) associated with central Pacific ENSO events can be different than the ones associated with the classical El Niño events. One issue is that, because of the relatively short historical record, we don’t have that many events of either category to compare and contrast. So, some of this is still up for debate and is an active area of research in the ENSO community.