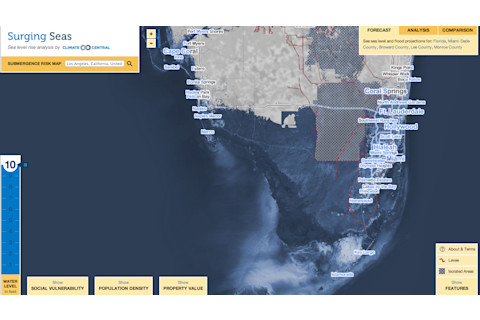

A screenshot from an interactive tool showing what Boston would look like with the 10 feet of sea level rise that would occur if the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet were to disintegrate. (Source: Climate Central) See a correction and update below. May 13 7:15 p.m. MDT | If you read ImaGeo regularly, you may have seen my post a couple of weeks ago describing evidence that part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet may be breaking up. Yesterday, two additional studies were made public. One was led by Eric Rignot, a glaciologist at the University of California, Irvine, who had this to say at a NASA press conference: “Today we present observational evidence that a large sector of the West Antarctic ice sheet has gone into irreversible retreat. It has passed the point of no return.” The likely cause: human-caused warming of the climate system. | Update: I'm doing further reporting on this for a future post. Among other things, I'm looking at the role that natural variation of the climate system, and other factors, may be playing. More on that soon. | The paper by Rignot and his colleagues, which examines the behavior of six West Antarctic glaciers that empty into a large indentation in the coast called the Amundsen Sea Embayment, has been accepted for publication in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. (Click here for a press release about the paper from the American Geophysical Union, publisher of the journal.) Ian Joughin, a glaciologist at the University of Washington's Applied Physics Laboratory, was lead author on the second study, which will appear in the May 16th issue of the journal Science. "There's been a lot of speculation about the stability of marine ice sheets, and many scientists suspected that this kind of behavior is under way," he says. "This study provides a more quantitative idea of the rates at which the collapse could take place." The sort of (but not really) good news: Joughin's study suggests that while the early stages of what it refers to as "collapse" may have begun, the rapid stage of collapse would not begin until at least 200 years from now, and possibly more than a thousand years down the road, depending on the warming assumptions made. full disappearance of one of the six glaciers, the Thwaites Glacier, could take at least 200 years. My colleague Andrew Revkin argues that given this time frame, use of the word "collapse" in this context, as some news outlets have done (for example, here), is a bit "overwrought." I get the point: On a human timescale, 200 years or more for the start of rapid disintegration is a very long time indeed. But on a geologic timescale, it is the blink of an eye. And that's important to keep in mind too — that in a blazing flash, geologically speaking, we humans are managing to remake the life support systems of our entire planet. This is why I think today's news will may eventually be seen as having historic significance. Another key fact to keep in mind about the study by Joughin and his colleagues: Thwaites is a linchpin for the rest of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, and its disappearance would likely trigger most if not all of the ice sheet to break up over a long period and flow into the sea. That would raise sea level by more than 10 feet. The screenshot at the top of this post, from an excellent interactive mapping tool at Climate Central, shows what Boston would look like if the water were to come up that much. Here's what south Florida would look like like:

A screenshot from an interactive mapping tool by Climate Central shows what South Florida would look like with 10 feet of sea level rise. (Source: Climate Central) In the United States, almost 5 million people live within just four feet of sea level today, according to the recently released National Climate Assessment. Globally, hundreds of millions of people live in areas that would be inundated by 10 feet of sea level rise.

To understand how that amount of sea level rise could occur, check out the video above. It does good job of visualizing how the apparently unstoppable destabilization of a large portion of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is now unfolding. Taken together, the two new research papers, and the one I wrote about earlier, add up to this sobering picture:

The glaciers that drain West Antarctica are speeding up faster than expected, dumping ever increasing amounts of ice into the ocean, thereby raising sea level. (This was the subject of the research I wrote a couple of weeks ago.)

Warming waters circulating beneath the glaciers are thinning the ice. This is causing their grounding lines — the points where they first lose contact with land as they flow out into the sea — to retreat inland. This, in turn, allows more water to circulate beneath the glaciers, contributing to thinning, and so on in a self-reinforcing process. (This comes from the paper by Rignot et al.)

Analysis of the bedrock beneath the glaciers shows there are no topographic features upstream of these grounding lines — no rocky hills, bumps, etc. — that could slow the glaciers and the retreat of their grounding lines. (Also from the Rignot paper.)

Lastly, Joughin and his colleagues used a combination of observations and modeling to show how long this self-reinforcing process would take to cause the Thwaites Glacier to drain into the ocean.

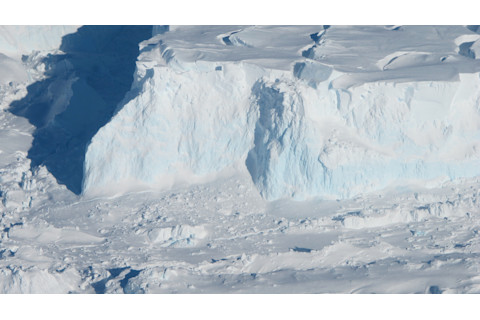

Photograph of the edge of the Thwaites Ice Shelf taken from a DC-8 aircraft on Oct. 16, 2012 as part of NASA's Operation Ice Bridge project. The blue areas visible on the shelf edge are areas of denser, compressed ice. (Source: NASA Earth Observatory. Photograph by Jim Yungel) Whether you believe yesterday's news will be eventually be regarded as an historic moment or not, it is yet another clear sign that human-caused changes to the planet once regarded as theoretical are now very real. And we should also be aware that the underlying geology and ice dynamics of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet are not unique. Yesterday I interviewed Jeremie Mouginot, a glaciologist at the University of California-Irvine and a co-author of the paper by Eric Rignot. He pointed out that while the much larger East Antarctic Ice Sheet is relatively stable right now and showing no signs of what's happening in West Antarctica, "the same kind of behavior could eventually happen there." Should that ice sheet become unglued, the challenge humanity would face from sea level rise would be unimaginably larger. Yes, we'd have a lot of time to plan for it. But do we really want to respond to the climate change impacts that are unfolding all around us simply by adapting? I'm thinking of my kids as I write the following words: That would be tragically irresponsible.