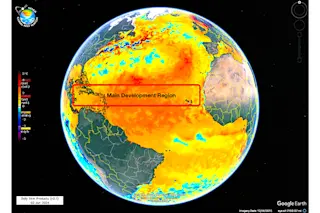

We can almost see it whole, the round-the-world journey that seawater takes. We can imagine taking the trip ourselves.

It begins north of Iceland, a hundred miles off the coast of Greenland, say, and on a black winter’s night. The west wind has been screaming off the ice cap for days now, driving us to ferocious foaming breakers, sucking every last ounce of heat from us, stealing it for Scandinavia. We are freezing now and spent, and burdened by the only memory we still have of our northward passage through the tropics: a heavy load of salt. It weighs on us now, tempts us to give up, as the harsh cold itself does. Finally comes that night when, so dense and cold we are almost ready to flash into ice, we can no longer resist: we start to sink. Slowly at first, but with gathering speed as more of us ...