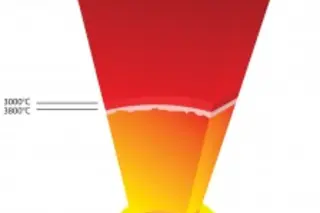

Artist’s view of the different layers of the Earth with their representative temperatures: crust, upper and lower mantle (brown to red), outer core (orange), and solid iron core (yellow). The pressure at the border between liquid and solid core (highlighted) is 3.3 million atmospheres. Image courtesy of ESRF. Scientists have a new window into the Earth’s core and how it behaves with research that shows the iron at the inner heart of the planet is heated to about 6,000 degrees Celsius---1,000 degrees hotter than previously estimated. For two decades, scientists have debated the details of the core’s temperature. Knowing its temperature is key to understanding the Earth’s internal processes, particularly its magnetic field and its geothermal activity. Now a research team, led by Simone Anzellini of the French national technological research organization CEA, has built an experiment that moved this elusive subject into the lab, re-creating the conditions at the center of the Earth. To do this, they placed a speck of iron between two small conical diamonds and applied almost 15,000 tons of pressure per square inch along with laser-beam heat to determine at what point the iron would melt. An X-ray diffraction technique continuously monitored the pressure, measuring deflected rays as the iron’s crystalline structure changed. The team was thus able to detect the tipping point of when the iron morphed from solid to liquid. The fast X-ray technique was essential in figuring out iron’s melting point. A sample of iron placed under intense pressure and extreme temperatures can change chemically in a matter of seconds, making the transition difficult to measure. “We have developed a new technique where an intense beam of X-rays from the synchrotron can probe a sample and deduce whether it is solid, liquid or partially molten within as little as a second, using a process known as diffraction,” says Mohamed Mezouar of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, “and this is short enough to keep temperature and pressure constant, and at the same time avoid any chemical reactions.” Knowing that the Earth’s core is under 3.3 million atmospheres of pressure, the researchers extrapolated their results in the lab to estimate the temperature at the boundary of the Earth’s inner core---the point where the core region’s fluid outer layer changes to a solid inner core. The team determined the temperature is 6,000 degrees Celsius, give or take 500 degrees. The findings are reported today in the journal Science.

Earth's Core is Much Hotter Than Scientists Thought

Discover how scientists estimate Earth's core temperature at 6,000°C, reshaping our understanding of geothermal activity.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe