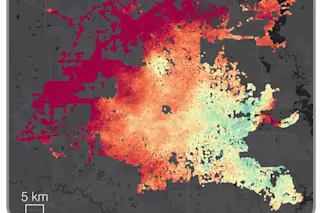

There are two basic points of view on global warming: it’s a problem or it’s not. In most of the world that argument is over and the pessimists have won, but not in the United States. And yet politically, if not scientifically, the argument seemed to be settled long ago—on October 15, 1992, to be precise, when the United States became the fourth country, after Mauritius, the Seychelles, and the Marshall Islands, to ratify the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. George Bush had signed the treaty at Rio de Janeiro four months earlier. It committed us to an objective: Stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. All the important details were missing; that’s what the meeting in Kyoto last December was all about. But as a nation we formally accepted the basic principle—global warming ...

Carbon Cuts and Techno-Fixes

10 Things To Do About the Greenhouse Effect (Some of Which Aren't Crazy)

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe