Coral reef at the Palmyra Atoll in the northern Pacific Ocean

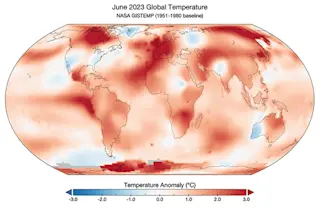

It’s not a good time to be a coral. Less than a third of coral reefs have legal protection from fishing and other damaging human activity. And as climate change increases oceans’ temperature and acidity, corals are suffering from more bleaching events, when stressed corals spit out the symbiotic algae they need to survive, and weaker skeletons. By 2050, coral reefs might be a lost cause. While some researchers work to protect reefs, others are preparing for conservation to fail---by collecting frozen coral sperm. As Michelle Nijhuis explains

in a New York Times article, marine biologist Mary Hagedorn is gathering reproductive material from many corals so that even as reefs die off, researchers can work at maintaining various species’ genetic diversity and trying to ensure their survival.

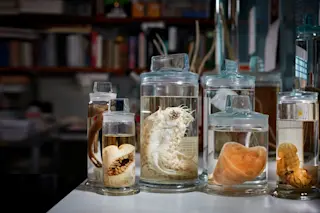

A reproductive physiologist with the Smithsonian Institution, Dr. Hagedorn, 57, is building what is essentially a sperm bank for the world’s corals. She hopes her collection---gathered in recent years from corals in Hawaii, the Caribbean and Australia---will someday be used to restore and even rebuild damaged reefs. She estimates that she has frozen one trillion coral sperm, enough to fertilize 500 million to one billion eggs. In addition, there are three billion frozen embryonic cells; some have characteristics of stem cells, meaning they may have the potential to grow into adult corals.

Of course, even Hagedorn’s trillion coral sperm pale in comparison to the diversity of corals living wild today. But as conservationists face daunting odds in the scramble to save coral reefs, keeping a backup policy on ice isn’t a bad idea. Head over to the New York Times article

to find out more about the dangers facing coral reefs, and the importance of saving endangered sperm.

Image courtesy of U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service / Wikimedia Commons