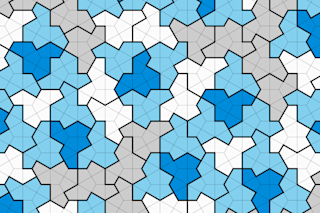

In the late 1970s, two mathematicians, John Conway and Simon Norton, saw a deep connection between two mathematical objects that should have nothing to do with each other. On one side of the link was a fundamental object in number theory called the j-function. On the other was a mysterious entity that described a new kind of symmetry, but might not even exist. If it did, though, it would be enormous (8x1053 components), so they dubbed it the “monster group.” The connection sounded so crazy, Conway and Norton called their theory “monstrous moonshine.”

In 1992, Richard Borcherds proved monstrous moonshine: He found the link between the monster group (which does exist) and the j-function through string theory, the idea that the universe is made of tiny strings vibrating in high dimensions. But monstrous moonshine, it turns out, was just the beginning.

In March, John Duncan, Michael Griffin and Ken Ono ...