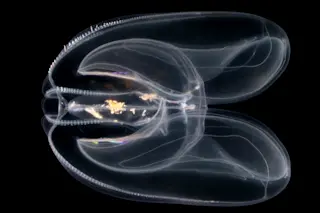

Some one-and-a-half-billion years ago, biologists believe, one of our single-celled ancestors engulfed a unique bacterium. Instead of becoming a meal, the swallowed microbe somehow managed to hang on inside that ancient cell and in its descendants, eventually evolving into a mitochondrion--the vital, energy-producing component now found in all animal and plant cells, as well as in fungi. There is plenty of evidence to back up the theory: mitochondria carry their own protein-coding DNA, and they divide by splitting in two, just like bacteria. Moreover, some mitochondrial genes and enzymes more closely resemble those of bacteria than those of their host organism. Now researchers have discovered what may be the theory’s clincher: the most bacterium-like mitochondrion ever found.

The ur-mitochondrion lives inside a unicellular mud-dwelling protozoan called Reclinomonas americana. Its circular string of DNA contains 62 protein-encoding genes, one-tenth the number found in any bacteria but far more than in any ...