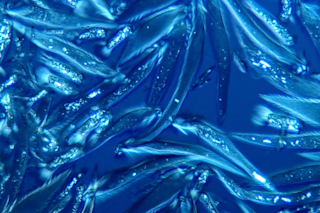

Cast your mind back to high school science class and you may remember peering through a microscope at a wee bacterium, which moved swiftly across the slide by spinning its flagellum around. The flagellum, a whip-like tail, acts like a rotary engine, and was previously thought that the only way for a bacterium to stop moving was to stop producing the proteins that form that tail. But according to a new study, bacteria actually stop by slipping out of gear with a molecular "clutch." The new insight into how bacteria come to a halt could help researchers prevent them from clotting together in undesirable places, like human lungs or medical equipment.

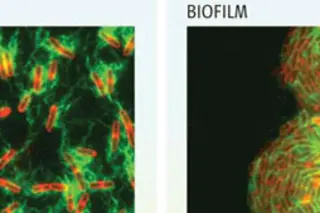

Many bacteria have two modes — either free-living and swimming, or settled down as part of a stationary 'biofilm'. These films are slimy bacterial cities only a fraction of a millimetre thick that contain vast numbers of cells and ...