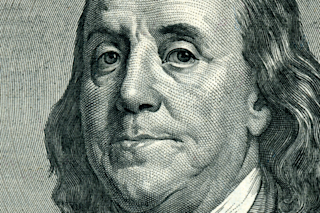

For more than two centuries, hundreds of human bones have rested (in peace) under the London home of Benjamin Franklin — one of the founding fathers of the U.S. But the secret of these bones isn’t quite as horrific as you might suspect.

As it turns out, the son-in-law of Franklin’s landlady taught anatomy privately in the house, at a time when the new field of science was just taking off in England. But that doesn’t mean the bones were completely innocent: The practice of dissection wasn’t strictly legal back then.

Read More: Ben Franklin: Founding Father, Citizen Scientist

The bones were first discovered in the late 1990s, while the Craven Street home underwent conservation repairs. The museum staff called a coroner, says Marcia Balisciano, the director of the Benjamin Franklin House, a museum at the former residence of Franklin in the heart of London, but the latter quickly the ...