It’s a hot summer day. You walk into your local brewery and order a gueuze — a sour beer with a dry feel and cidery aroma. Little do you know that the yeast responsible for the drink is famous for producing pungent notes of wet dog, horse blanket and rope. Brettanomyces, affectionately referred to as “Brett,” sounds disgusting. But with the right balance, it can lift a brew to new heights.

Yeasts are the “engine at the heart of the brewing process,” says Kevin Verstrepen, a geneticist at the Vlaams Institute for Biotechnology and the Leuven University in Belgium. During fermentation, the single-celled fungi eat sugars and spit out alcohol, aromatic compounds and carbonation. As zymologist Quinton Sturgeon put in during an episode of the podcast “Ologies,” beer is just “yeast farts and piss.”

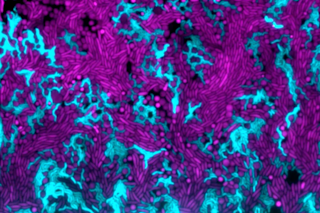

The workhorse yeast that ferments most beers is called Saccharomyces — the genetics model that you’ll ...