Pliny the Elder, the Roman savant who compiled the eclectic 37-book encyclopedia Historia Naturalis nearly 2,000 years ago, was obsessed with the written word. He pored over countless Greek and Latin texts, instructing his personal secretary to read aloud to him even while he was dining or soaking in the bath. And when he traveled the streets of Rome, he insisted upon being carried everywhere by slaves so he could continue reading. To Pliny, books were the ultimate repository of knowledge. "Our civilization—or at any rate our written records—depends especially on the use of paper," he wrote in Historia Naturalis.

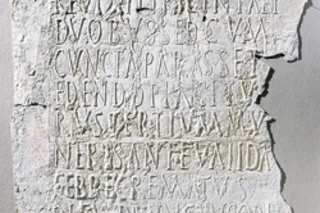

Pliny was largely blind, however, to another vast treasury of knowledge, much of it literally written in stone by ordinary Romans. Employing sharp styli generally reserved for writing on wax tablets, some Romans scratched graffiti into the plastered walls of private residences. Others hired professional stonecutters to engrave their ramblings ...