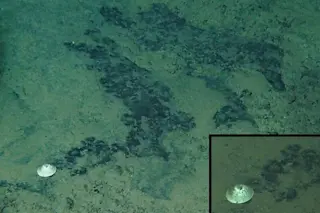

Late in the cold war, the United States Navy decided it would be a good idea to survey the altitude of the ocean surface, all over the world, to within a few inches. The point was not to measure waves. The ocean is not flat even where it is calm: it has hills and valleys that depart by as much as a few hundred feet from what we think of as sea level. The slopes of these features are so gentle--they extend over tens or even hundreds of miles--that no ship ever feels them. Yet the Navy decided that submarine commanders, of all people, would benefit from precise measurements of this imperceptible topography.

Why? Because the study of bumps on the ocean surface is a reliable kind of phrenology: it reveals deeper truths about the ocean. Small, shifting bumps are created by the shifting fronts between water masses--between the warm ...